Tom Wood –

People often describe certain fixtures operating “differently” from others. Most will argue that there is often a different atmosphere surrounding a match, a different mindset possessed by both player and supporters alike going into a game. The Old Firm in Scotland, the Superclasico in Argentina, El Classico in Spain, all individually possess certain qualities that enable the respective fixture to distinguish itself from the average intercity derby. Never before, however, have I experienced first-hand, a fixture that is different in almost every conceivable way, as is Serbia’s Eternal Derby between the nation’s two biggest sides, Red Star Belgrade and Partizan Belgrade.

In Budapest the week before the Eternal Derby took place, I had witnessed less than half of the epic thrill ride of an encounter between Ferencváros and Videoton (which finished 0-0) because of the lengthy queue for a membership card that you needed to purchase a home ticket. Whilst the staff in the ticket office were more than helpful when it came to assisting me, and a group of English speaking Hungarian Ferencváros supporters in the queue provided me with company, conversation and even a stream of the game via an IPhone, I was left rather dejected by the experience. For me, therefore, in a footballing sense, Belgrade was Eastern Europe’s second chance. As my train rolled through the fields of rural Hungary across the border into Serbia, past the mighty Petrovaradin Fortress of Novi Sad, Vojvodina’s ethnic heartland, and finally began to approach the bustling outskirts of Belgrade, I could almost taste the scent of redemption in the smoky evening air.

The Marakana in Belgrade was the scene of the latest Eternal Derby (ANDREJ ISAKOVIC/AFP/Getty Images)

The following day, after a much needed rest, I took the short journey to Stadion Rajko Mitic, the home of Crvena Zvezda. It is certainly true that Brazil’s football culture made a huge impression on Yugoslavia’s game. In Croatia, the name of Hajduk Split’s notorious fan group, ‘Torcida’, is taken from the Brazilian term for a hooligan firm, ‘Torcidas’. In Belgrade, most Serbs, regardless of their alliance, will refer to Red Star’s stadium as the Marakana, which references Brazil’s own classic Maracanã stadium. A very striking aspect of the ground is its location. Situated about 20 minutes south of Republic Square, it is less than a kilometre away from Partizan Stadium, the home of their arch rivals, Partizan Belgrade.

The Eternal Derby – Two Clubs that are constantly up in arms with each other

For anyone not familiar with Serbian football, it is striking to witness two clubs that are constantly up in arms with each other, yet, although neither side will admit it, are so similar. Both football clubs were established in 1945, the products of hope in the dying embers of the worst conflict in human history. Both clubs were also established by staunch anti-fascists, Red Star out of the ruins of SK Jugoslavija, who had committed the crime of playing under German occupation, and Partizan who were forged by a number of decorated Generals and became Yugoslavia’s official Army Club after the Dalmatian Hadjuk Split rejected Tito’s attempts to move them from their home on the Adriatic. Furthermore, both clubs had grand European heydays. Yugoslavia’s First Division was an extremely competitive one and in the league’s duration, in addition to Red Star Belgrade and Partizan Belgrade, teams like Dinamo Zagreb, Hadjuk Split, Velež Mostar and FK Sarajevo emerged and built credible reputations as competitive European sides. However Partizan of the 1960’s and Red Star’s European Cup winning side of the 1990’s, firmly stand head and shoulders above the rest.

Despite the fact that I spoke very little of the language, it only took a single taxi journey to truly understand how embedded the two generations of footballers were to the average Serbian. I only had to mention the name Dejan Savićević, for my driver, Boris, an apparent fanatic Red Star Belgrade supporter, to break out into a wry smile, and with an excited and affectionate tone respond with, “Siniša Mihajlović!”.

At the point of Red Star’s European Cup success in 1991, Yugoslavia’s breakup was almost certainly in the cards. Within a month of the final, Slovenia had declared independence and, on the same day, Croatia took their most important constitutional steps towards independence to date. The amazing victory of a Serbian Club, therefore, on the grandest stage of all, probably gave impetus to those trying to push a nationalist agenda in Belgrade. However, it’s important to remember that winning Europe’s premier competition was achieved not only with talented Serbs but also with a Croatian, a Montenegrin, a Macedonian, and a Romanian in exile, along with many other individuals who weren’t Serbian natives, all playing vital roles in the team. Whilst nationalism was tearing Yugoslavia apart, Zvezda’s band of brothers, who still have arguably one of the most nationalist fan bases in world football, were ironically upholding Tito’s dying dream of a united country—men from different ethnic backgrounds fighting side by side for a shot at making history.

Red Star Belgrade are like the Icarus’ of Eastern Europe

Red Star Belgrade, like Steaua Bucharest who came before them, is one of the many Icarus’s of Eastern Europe. Flying so very high, the Serbians went from European Cup success to crashing down into a sea of severe financial trouble and underachievement, scorched by the heat of nationalism, corruption and war that swept the country over the next 10 years. By the end of 1992, almost the entirety of the starting XI that conquered Europe had left the club.

The likes of Darko Pančev, Dejan Savićević and Siniša Mihajlović had moved to Seria A on lucrative deals, whilst Robert Prosinečki joined the Spanish giants Real Madrid in La Liga. Sanctions imposed on Serbia by the European community damaged Crvena Zvezda significantly and the club haven’t qualified for the group stages of the now Champions League since 1992. Monetary farce has descended onto the club on numerous occasions over the past decade. The club were suspended from the UEFA Champions League in 2014 over unpaid debts, which by 2015 had amounted to over €40 million for a whole season. City rivals, Partizan Belgrade, have been a lot more successful in European competition in recent years qualifying regularly for both tiers of European Competition. They too, however, have felt the wrath of UEFA on several occasions and, earlier this year almost faced an extended ban for breaching financial regulations for the third time in five years.

A maintenance worker drives past a mural at the Red Star Belgrade Marakana stadium on April 27, 2016, 25 years after the Red Star Belgrade European Cup final, an apotheosis of Yugoslav football before the country’s bloody collapse. When the crowd hailed Pancev’s final goal, the football legend, Red Star technical director at the time Dzajic, opened his eyes to fall into the arms of coach Ljupko Petrovic. The club, where he remains the top scorer, is now only a shadow of what it once was. The same as Marakana which was proud of its capacity of 100,000 people. (ANDREJ ISAKOVIC/AFP/Getty Images)

These financial problems and lack of success on the European front can be attributed to a wealth of factors. One factor that sticks out particularly, however, is the lack of privatisation opportunities readily available for Serbian clubs. Both Partizan and Red Star are partly owned by the state and, with politicians still a long way from passing a Privatisation Act, it seems that Serbia’s two biggest clubs will have to endure financial instability, a severe lack of resources—all the fabulous bonuses that come with a private owner, such as a sustainable amount of capital.

It’s important to point out that the only club that has been privatised in Serbia’s Superliga, as of yet, FK Čukarički, is by far the most sustainable business model. As a direct result of a takeover by the construction and wholesale company, ADOC, supporters have not only been rewarded with a rapid rise back to Serbia’s top flight and a Serbian Cup in a brilliant last few seasons, but also the players and staff have been blessed with regular payment and secure jobs.

Another important factor in the demise of Yugoslavian football, quite obviously, was the breakup of the country and, therefore, of the league. With Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Slovenia all forming different leagues, Serbian sides have lost the opportunity to test themselves against the likes Dinamo Zagreb, Hadjuk Split, FK Rijeka, SK Sarajevo and FK Željezničar. Some will argue that this is a rather good thing, as big security problems emerge from fixtures involving Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian sides. Historically, matches that have included Yugoslavian football’s big four—Red Star Belgrade, Partizan Belgrade, Dinamo Zagreb and Hadjuk Split—have all been flashpoints for violence.

Football and politics are always closely interconnected in this part of the world

One game in particular, that took place between Crvena Zvezda and Dinamo Zagreb on the May 13, 1990 will be cemented in footballing notoriety for centuries to come. The events at Stadion Maksimir that day saw men from both supporter groups, Red Star Belgrade’s Delije and Dinamo Zagreb’s Bad Blue Boys, take centre stage, as an overabundance of nationalism and pent up tension spilled over in Croatia’s capital. With the match, all but called off before the second half, mass rioting, weapons, rocks and violence between supporters engulfed the terraces and the pitch.

Clashes were particularly intense between Zagreb’s BBB and the police who had been deployed to calm the tensions and who were perceived as being mostly Serbian. The beating of one Croatian fan on the pitch led to one of football’s most iconic moments. Former outspoken Dinamo Zagreb captain turned FIFA Deputy Secutary General, Zvonimir Boban, fly kicked a policeman (who turned out to be a Bosniak Muslim), earning a one year ban from the Yugoslavian national team and simultaneously establishing his place in Croatian folklore.

The event is romanticised by football supporters—many proclaiming the riots to be the explosion that ripped apart the fabric of Yugoslavia. However, in reality it is rather naïve to believe that a single football match could have had this effect. The creeping tide of nationalism wasn’t a mere surge at the end of the 1980’s. Tito had tried his upmost to squash any sort of nationalist movement that gained momentum during his period of control. After his death there was less authority to suppress such sentiment and arguably less reason to remain together. The football match should be seen more as a moment of symbolism. It was an event that reflected the national mood, but not the powder keg that ignited an entire war.

When generalising about Serbia and Serbian football supporters, it’s also rather easy to generalise that every fan in the country is a right-wing anarchist with a thirst for violence and hooliganism. As I learnt quickly, when I was collecting the media pass for the Derby, this view could not be further from the truth. At Red Star’s fan shop, I thoroughly enjoyed talking to two of the employees at the club about my own team Tottenham Hotspur and the state of our respective domestic leagues, and even offered to swap scarfs at the end of the conversation.

During my time in the media centre, I was treated well by the staff and had some excellent conversations with several English-speaking Serbs. My stay in Serbia was incredibly pleasant and, during the week I was there, I met some of the most hospitable people I’ve come across in my life. It is vital that people do not simply believe the stereotypical message that media outlets spew out about certain countries. As we have seen recently regarding the BBC’s sensationalist documentary about football hooliganism in Russia, hysteria can easily be generated by manipulating facts and directing a spotlight onto biased coverage, thereby, not only generating high television ratings but also creating a level of deceit over the truth.

Serbia is often unfairly portrayed in the media

The perception of Serbia as the far right nationalist pariah of Eastern Europe who are unwelcoming to foreigners and still in a state of perpetual war almost two decades after the NATO’s bombing campaign ended, is, unfortunately, still a view that is generally held by many in the United Kingdom who aren’t clued up on the region. Experiencing different cultures with an open mind is the better option, and I certainly got more out my trip using this approach.

Earlier in the article I alluded to the word “different” as an essential term when one is looking for words to try and describe the confusing and wild atmosphere surrounding a game. It was match day, and as the Marakana edged into view, I could only gawp as I gazed onto the columns upon columns of riot police who were scattered around the streets. “Look, turtles you see?” joked our friendly taxi driver, pointing to the shell-like body amour present on the riot police. The uncanny resemblance failed to crack a laugh in the tense evening atmosphere, as our taxi was surrounded out by a sea of leather boots and weapons. This truly was a “different” fixture.

Partizan Belgrade’s goalkeeper Filip Kljajic (R) hugs Brazilian midfielder Everton Luiz as he leaves the field in tears (STR/AFP/Getty Images)

Partizan Belgrade, in particular, were facing several fresh problems since returning from the SuperLiga Winter Break. Only a week before the game, Brazilian Everton Luiz was racially abused by FK Rad supporters. Even FK Rad’s Vice Chairman, Jelena Polić, got involved with the abuse, and stated in an explicit tirade on Facebook that Luiz should “go back to Brazil” and show his “dark fingers” elsewhere. Even more shocking, Partizan’s own manager, Marko Nikolić, actually condemned Everton’s in responce to the racist tirade that he had received. Nikolić, who was dismissed from his last managerial position at NK Olimpija Ljubljana over an incident of racism towards one of his own players, hardly has an excellent moral track record and his response is not surprising. As discussed earlier, Partizan have also had to deal with the threat of being excluded from European Competition over unpaid debts, so it has been a cold unexpected shower of a start to the second half of their SuperLiga campaign.

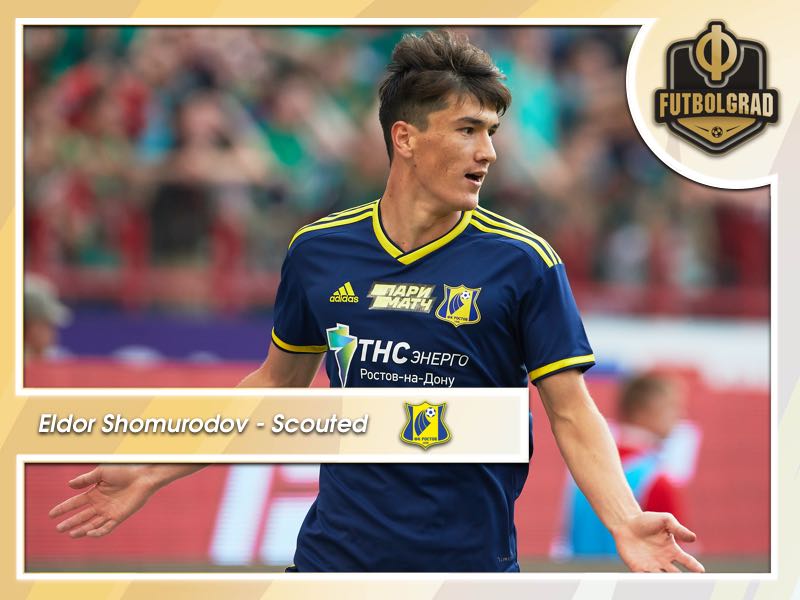

Despite his stupendous sending off, which many Red Star fans argue was a key factor in Zvezda’s 4-2 loss to Ludogorets at home in this season’s UCL playoffs, Guélor Kanga has impressed in his first season at the club. The more recent addition of Ghanaian striker Richmond Boakye on a loan over the winter break has proved an astute purchase, the ex-Juventus man riding a wave of form with 2 goals in his first 2 games as the derby approached.

This particular Eternal Derby also marked 39-year-old Partizan legend, and record appearance holder, Saša Ilić’s 29th individual Derbi. Ilić who came through Partizan’s youth system, returned to Partizan after spells in Turkey, Spain and Austria in 2010 and is already regarded as one of the club’s greatest-ever players. Partizan Belgrade, in particular, have a track record for producing incredibly talented footballers. The likes of Lazar Marković, Stevan Jovetić, Andrija Živković, Aleksandar Mitrović, and Adem Ljajić all came through the Crno Beli ranks.

The latest to emerge from the seemingly endless conveyor belt of talent, 19 year old center-back, Nikola Milenković, who was recently snapped up by Fiorentina, was able to display his talent at the Eternal Derby that took place on the birthday of Red Star Belgrade. Like Partizan, Red Star have lost their fair share of talented players over the last season.

Marko Grujić was sold to Liverpool, Luis Ibáñez to Trabzonspor, Aleksandar Katai to Deportivo Alavés and Hugo Viera to Yokohama F. Mariners, not only stripping the team of talented players, but also players who were key to the way that their manager, Miodrag Božović, sets up. Losing players is a guaranteed by-product of a drop in overall competition. For the Superliga to truly be able keep their best players away from the clutches of the Premier League, Seria A and La Liga, or even to actually nurture properly and then sell promising talent for a great deal more than what’s happening currently, the league needs to be remodelled and enhanced. Without privatisation, the investment of capital and the elimination of negative elements like the corruption that riddles the country’s game, the future of Serbian domestic football appears rather bleak.

Could a Balkan League fix football in the region?

One idea that’s certainly been touted on a number occasions has been the formation of a “Balkan League”. In early December of last year, the rumour mill was truly in full swing. Macedonian Football League Director, Vasko Dojcinovski, came out and reportedly suggested that UEFA had approved the idea. Whilst UEFA’s president has openly rebutted the idea since, the rumours have continued to build and the possibility of a Balkan League existing by the time the current Champions League television deal ends, is more likely than ever before.

To a lot of people, the idea of the league is fantastic. A Balkan League means that immediately, sides of a higher calibre than those in domestic leagues alone will be taking part, significantly raising the level of competition for all Balkan countries. The glamourous fixture possibilities would add further prestige to the league and would give it an element of hype. This could make the league incredibly attractive for private investors, ease the burden on the state, and provide a secure financial future to football clubs in the region that aren’t already privately owned.

However, like most things in the Balkans, there are complications that will certainly arise. The cost of policing and travelling to the games would be enormous. Fan violence would arguably be rife and some sceptics even argue that only a few teams in the region play at a high enough standard to help raise the general game in the area. In their current state, for example, no clubs outside of Croatia would push to improve Partizan or Red Star’s game. Ultimately, there does seem to be a significant lack of positives emerging from the idea of a Balkan League. I spoke to five different reporters in Red Star Belgrade’s Media Centre, including two Serbs and a Croat, all of whom strenuously opposed the league’s formation. For someone who had previously been a strong advocate of the idea of a Balkan League, it was surprising to see such an overwhelming decision against the move.

So with both sides lacking the raw talent of the likes of Marko Grujić and Andrija Živković who had featured in derby’s of days gone by, and the Eternal Derby taking place almost straight after the Serbian winter break, it would have been quite astute to assume that the crowd would have been in for a very boring day. However, if one has truly come to sample footballing quality from Belgrade, and footballing quality alone, then I’m afraid they’ve come to the wrong place. Why analyse tactics and smooth passing, when you can analyse the extraordinary scenes taking place all around you in the stands. Certainly, the atmosphere was indescribable.

Visiting the Eternal Derby

Partizan’s away support was on the grounds hours before kick-off of the Eternal Derby and the South section of the stadium was creating quite the ruckus. In recent years, a seismic split has occurred within the Grobari. Alcatraz, named because of the uncanny resemblance of Partizan’s black and white strip to a classic prison outfit, Grobari’s main subgroup, have been accused by a collection of other Grobari groups, collectively known as The Forbidden, of racketeering and co-operating with police at the expense of other Partizan fans. Many members of The Forbidden have seen themselves almost completely exiled from their own stadium and Alcatraz have a big part to play in this. Clearly, tensions are still very high between the feuding groups, and it was odd to witness so many riot police separating fans of the same team. Even stranger however, was how quickly the two groups could toss aside their own differences and unite under the guise of hatred for their city rivals. Heavy chanting directed to the Delije, continued for what seemed to be a lifetime. Red Star Belgrade had a very impressive pyrotechnic display before the game began, and the sight of more than 30,000 Serbs screaming out the club’s anthem, which spilled over until after kick-off, could give goosebumps to even the most apathetic individual.

The Eternal Derby is always a heated affair. (ANDREJ ISAKOVIC/AFP/Getty Images)

The Eternal Derby was rather slow getting started and neither side seemed to settle down a great deal, until the first real opportunity came from Zvezda playmaker, Srđan Plavšić, who, with a great turn of pace, carried the ball effectively into the box. Plavšić, a player renowned in the league for his fantastic dribbling ability and a measure of speed, is, however, somewhat hindered by his lack of physical strength, and was booked for diving as the move broke down.

Red Star, in general, then began to get into the swing of things and, after the Eternal Derby was halted for a period to let Partizan’s fiery pyro storm blow over, started to properly take charge. Some great work from John Ruiz saw him cut back to the in-form Guélor Kanga, who had actually started the game off poorly, to precisely finish for 1-0, sending the Marakana into raptures, the Delije responding appropriately with some very lively celebrations in the north stand of the ground.

After half time, Zvezda stepped up the pressure looking for the second goal, and until the 87th minute of the game, looked very likely to see the match out. However, only minutes after those in the North Stand let off a sequence of flares and smoke bombs in a rather pre-emptive victory celebration, Partizan’s man in form, former Palermo and Vitesse striker, Uroš Đurđević, finished after an excellent ball on from the right flank. This almost sparked a compete resurgence from the away side and Partizan looked as if they would go on to win the game. However, the lack of precise passing in the final third let them down, as it did largely for both teams on the day, and the score remained 1-1.

The Eternal Derby shows that football is more important than that

What did become came clear in the aftermath of the Eternal Derby was that neither goal, in fact, should have stood, Ruiz clearly ran the ball out of play before cutting back to assist, and Đurđević handled the ball on its way into the net, meaning that I had effectively travelled all the way to Serbia to watch a 0-0 draw. And, to be honest, I was not even bothered. During 90 minutes of the Eternal Derby, I had been through an emotional rollercoaster of excitement and thrills, my face and my laptop were covered in a layer of black dust from the various pyro displays that took place. This Derby was the deep end of the swimming pool, a game unto itself.

Part of me worries significantly about the problems that all teams are facing in Serbia, and the endless dilemmas that are not solved and the proposed solutions that do not work. I don’t want to see Serbia’s domestic game fade away and the promised land of the UEFA Champions League slowly become an unachievable fantasy for any club in The Balkans. I am worried. But what I’m certainly not worried about is the fighting spirit and the passion of both sets of supports. In fact, I do not doubt the sincerity of the support of any team in the entire region and, as long as this abrasive, terrifying but rather beautiful tradition of following one’s team continues in the region, people will stay interested, people will keep coming and people will recognise the dedication on show. As Bill Shankly once famously said, “Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that!”—and on this occasion and for the supporters of both Crvena Zvezda and Partizan Belgrade, it rings very very true.

Tom Wood is from South Benfleet Essex, and is currently an A Level Student at Southend High School For Boys, hoping to study History and Eastern European Studies at degree level.Tom is a long suffering but devoted Tottenham Hotspur fan,who is also passionately interested by the culture and politics of European and Eastern European football.Tom is particularly interested in football played in the Balkans, and is fascinated by the immense role that football supporters played in contributing to Yugoslavia’s breakup and the subsequent wars that followed. Follow Tom on Twitter @EFJtomwood

COMMENTS